The Crime of Being Black In America

We need to challenge the assumption that racially-driven policing ended after the Civil Rights Movement.

We need to challenge the assumption that racially-driven policing ended after the Civil Rights Movement.

Note: this post was republished from the author’s blog.

Over the past months, we’ve watched several cities experience the fallout from law enforcement officers ending the lives of black men. Are the protests justified? Should we be concerned about systemic racism in our justice system?

The short answer is yes. Not only should we be concerned, we should be alarmed and outraged by the sheer magnitude of the problem. I’ll be spending the next several thousand words unpacking the why behind that “yes”, since the insidious nature of systemic racism makes it extremely difficult to point to a specific incident or statistic that would definitively prove things one way or the other. Rather, we must examine a larger pattern of trends and data to allow a constellation of facts to emerge.

The Usual Caveats

I am a young white male, in the upper-middle class. Chances are, if you’re reading this, you probably also fall into at least a few of the same circles on the Venn diagram of “why you will probably never have a negative experience with the police.” As a writer, therefore, I must acknowledge the limits of my personal experience and rely on the stories and data of others to create this narrative. Likewise, if you’ve never been arrested, searched, or held by the police, I would ask you to read with an open mind and not automatically discount the information presented here simply because it has not been true for you in your personal experience.

I also feel obliged to note that I know several people who are either currently or formerly in law enforcement. I’m proud to call all of them friends, and I truly believe that they have done their level best to serve their communities and keep us safe. I would suspect that many of us know some great police officers, and I certainly don’t intend to argue the strawman that “all cops are bad.” Rather, I would argue that there are some extremely well-meaning individuals working within a completely broken system that allows bad individuals far too much leeway to overshadow their colleagues’ intentions with abusive behavior.

The Opening Questions

This post was triggered by a series of questions posed to me by a friend on Facebook after I’d shared an article on the Baltimore riots. After running out of characters in my reply to the comment, I decided it would just be simpler to post here. The questions I’m attempting to address today are as follows:

Are the police somehow any worse than any other occupation when it comes to corruption, temptations, or poor decision making? Are they somehow more racist than any other occupation? Do these instances of white officers killing young black men indicate racism or just the probability of statistics? When looking at the percentage of white officers to the black communities they work in would you really find anything statistically significant? Should there be cries of injustice and rioting in the streets by white folks in Boston after the brutal shooting in the face of a white police officer by a young black man after being pulled over? Have instances of police brutality and violence in general increased in the last year or so, or are they just getting more attention right now; especially white on black? And if that’s the case then why? Does any law abiding black person in Baltimore really need to be afraid of the police? Does any law abiding person of any color really need to be afraid of the police anywhere?

Telling A Story With Numbers

To start with, let’s just examine some statistics:

Under New York City’s “stop and frisk” policy (where police can detain and search anyone without having reason to believe they were engaged in a crime), Black or Latino individuals were detained 80% of the time despite making up only 25% of NYC’s population.

Likewise, under Chicago’s stop and frisk policy, Black individuals were detained 72% of the time despite making up only 32% of the population.

Black drivers are 31% more likely to be pulled over than White drivers. Once pulled over, Black drivers are statistically more likely to be given a ticket than a White driver pulled over for the same offense.

Black drivers are also 3 times more likely to be searched during a traffic stop than White drivers.

While Black and White individuals use marijuana at approximately the same rates, a Black person is 3.7 times more likely to be arrested for possession.

In Ferguson, MO, Black drivers were more than twice as likely as their white counterparts to be searched during vehicle stops, but 26 percent less likely to have contraband.

I’m going to pause here and note that these statistics are strictly about race, not socioeconomic status. Poverty plays a significant factor in the likelihood that a particular individual will commit a crime (more on that later), but suffice it to note that Blacks are almost 3 times more likely to be stuck below the poverty line than whites (27% compared to 10%).

Life With An Abusive Police Department

What exactly does it look like when a police department engages in systematic abuse of minorities and disadvantaged populations? A few case studies may serve to illuminate life in a broken system.

Cleveland

A 2014 investigation by the Department of Justice “concluded that there is reasonable cause to believe that CDP engages in a pattern or practice of using unreasonable force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.” That pattern manifested in a range of ways, including:

The unnecessary and excessive use of deadly force, including shootings and head strikes with impact weapons

The unnecessary, excessive or retaliatory use of less lethal force including tasers, chemical spray and fists

Excessive force against persons who are mentally ill or in crisis, including in cases where the officers were called exclusively for a welfare check

The employment of poor and dangerous tactics that place officers in situations where avoidable force becomes inevitable and places officers and civilians at unnecessary risk.

These findings were included in a consent decree in which the Cleveland Police Department agreed that their officers would no longer hit people in the head with their guns. Just let that one sink in for a second. A police department had to be legally compelled not to pistol-whip arrestees.

Cleveland is the city where Tamir Rice, a 12 year old boy, was fatally shot by police while playing in the park. The officer shot Rice within seconds of arriving on the scene.

It’s also where Tanisha Anderson died as a result of being forcefully restrained by a Cleveland police officer. Anderson, who was mentally ill, was supposed to be transported to a nearby hospital at the request of her family.

Most infamously, it’s the city where Marissa Williams and Timothy Russell were killed when police fired at least 137 shots into their car after a high-speed chase — including one officer who jumped up onto the hood and fired multiple rounds directly through the windshield. Both Williams and Russell were unarmed.

Philadelphia

A report by the Department of Justice found that there was an 8.8% chance that Philadelphia police would mistakenly shoot an unarmed Black person, compared to a 3.1% chance that an officer would mistakenly shoot an unarmed White person. The report goes on to note that “Incidents involving discourtesy, use of force, and allegations of bias by officers leave segments of the community feeling disenfranchised and distrustful of the Police Department. Distrust in the ability of the [Police Department] to investigate itself pervades segments of the community. Scandals of the past and present, high-profile [shooting] incidents, and a lack of transparency in investigative outcomes help cement this distrust.”

Philadelphia is also infamous for their practice of “nickel rides,” where an arrestee is placed in a paddywagon without any restraints and then given a rough ride across the city — often with horrifying results. The injured include:

A disabled postal worker who had argued with a police officer over access to a parking lot. She aggravated a hip injury rolling across the floor of a wagon.

A pastor who saw police subduing a suspect and complained that they were hurting him. She was arrested and loaded into a wagon, where she fell to the floor during a swerving, bumpy ride.

A fish merchant arrested after arguing with a Parking Authority worker over a ticket. He was thrown from a wagon bench and broke his tailbone.

Gino Thompson, arrested outside a North Philadelphia convenience store after a drunken argument with a girlfriend over a set of keys. Police put him in the back of a patrol wagon, his hands cuffed behind his back. As the wagon headed south on Broad Street, toward the 22d District police station, the driver accelerated and then came to a screeching stop. Thompson was launched headfirst into a partition and suffered a devastating spinal-cord injury.

Calvin Saunders, arrested in South Philadelphia in 1997 driving a stolen car, was propelled from his seat in the back of a police van and rammed his head against a wall. He ended up a quadriplegic, paralyzed from the neck down. To this day, Saunders cannot feed, bathe or dress himself and depends on others for his most basic needs. The city paid him a $1.2 million settlement to help cover his lifetime medical care.

Philadelphia also agreed in 2011 to stop performing stop-and-frisk searches on Black and Latino men when the practice was declared unconstitutional after a Federal lawsuit, yet 37% of the pedestrian stops done by police in 2014 were conducted without a suspicion of wrongdoing.

Chicago

Chicago is the home of Homan Square, an off-the-books detention and interrogation facility run by the Chicago Police Department that has been compared to “a CIA black site.” Abuses at Homan Square include:

Keeping arrestees out of official booking databases.

Beating by police, resulting in head wounds.

Shackling for prolonged periods.

Denying attorneys access to the “secure” facility.

Holding people without legal counsel for between 12 and 24 hours, including people as young as 15.

At least one man was found unresponsive in a Homan Square “interview room” and later pronounced dead.

Kory Wright, Deandre Hutcherson and David Smith, all Black men, described their experience being held in Homan Square:

“They had me handcuffed — both hands stretched-out,” Wright told the Guardian. “I was stretched out like I’m being crucified.”

The position left Hutcherson defenseless when an officer he said grew frustrated with interrogating him and punched him two or three times in the face.

“He takes his foot and steps on my groin, like he was putting out a cigarette or something, with his toe,” Hutcherson told the Guardian. Before leaving, the officer said, “it’s gonna get a little hot up in here,’” Hutcherson remembered. The officer closed the door and soon Hutcherson began sweltering from the heat in the stifling room.

Their crime? Wright had agreed to make change for a $50 bill for an undercover police officer so she could ostensibly go buy drugs.

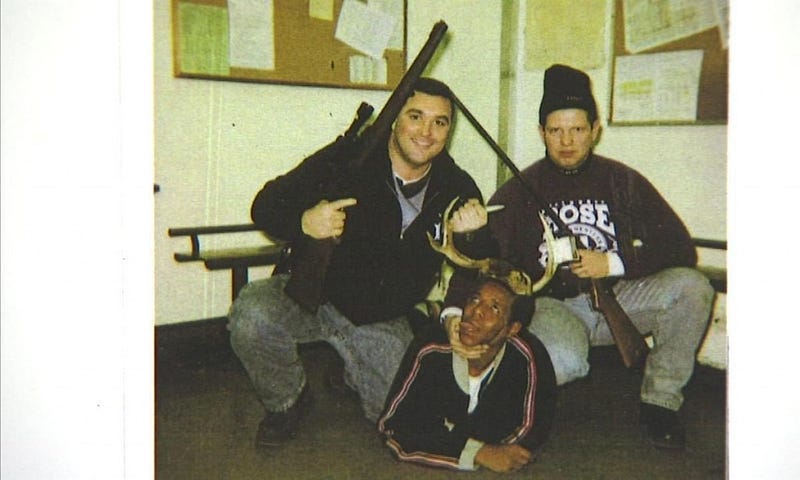

Just recently, a photo surfaced of two Chicago police officers posing a Black man as a hunting trophy:

Chicago is also still recovering from the legacy of Jon Burge, a Chicago police commander who oversaw the torture of more than 100 Black men throughout the 70s and 80s. This is the story of Darrell Cannon:

Darrell Cannon’s 31-year quest for justice began in November 1983, when he was arrested for the murder of a drug dealer by a contingent of midnight-shift detectives who worked for Jon Burge. They allegedly dragged him to a police car, where Cannon says Detective Peter Dignan told him that they had a “scientific way of questioning n*ggers.” When Cannon refused to talk, he says Sergeant John Byrne, who was Burge’s self-admitted “right hand man,” and Dignan took him to a remote site on the far southeast side of Chicago, where they enacted a mock execution. After pretending to put a shell in his shotgun, Cannon recounts that Dignan forced the barrel of the gun into his mouth and pulled the trigger. Dignan allegedly repeated this action two more times. On the third, Cannon says he believed that the back of his head had been blown off.

When Cannon still refused to confess to the murder, he says, Byrne and Dignan threw him into the backseat of their car, pulled down his pants, and repeatedly shocked him on the genitals with a cattle prod. Racked with pain, Cannon agreed to cooperate; after the torture stopped, he withdrew his agreement. Cannon alleges that Byrne and Dignan then administered another round of electric shocks, this time shoving the cattle prod into his mouth. Cannon then relented and gave a false confession that implicated himself in the murder.

[…]

Over the past 40 years, state and federal courts as well as prosecutors have very seldom been open to providing fair justice to the African-American survivors of Burge-related police torture. More than 100 were sent to prison — a dozen to death row — on confessions tortured from them. At least 20 remain there, some 25 to 30 years later.

Burge spent less than 4 years in jail for his role in overseeing the torture, and still receives a pension from the city.

“The subtle message in the department is white supremacy, white male supremacy,’ said Pat Hill, a Chicago police officer from 1986 to 2007 who led the African American Police League. “The type of crime that they’re supposed to be fighting is described for them, and the face of the criminals are black.” When Hill tried to resist it within the African American Police League, she said she faced retaliation: not only was she called racist names, she recalled, but cocaine and marijuana began showing up in patrol cars she had used during routine inspections.

Baltimore

In an investigation by the Baltimore Sun, the newspaper found that the city has paid out almost $5.7 million in settlements related to police violence against residents since 2011:

Victims include a 15-year-old boy riding a dirt bike, a 26-year-old pregnant accountant who had witnessed a beating, a 50-year-old woman selling church raffle tickets, a 65-year-old church deacon rolling a cigarette and an 87-year-old grandmother aiding her wounded grandson.

Those cases detail a frightful human toll. Officers have battered dozens of residents who suffered broken bones — jaws, noses, arms, legs, ankles — head trauma, organ failure, and even death, coming during questionable arrests. Some residents were beaten while handcuffed; others were thrown to the pavement. And in almost every case, prosecutors or judges dismissed the charges against the victims — if charges were filed at all.

Such beatings, in which the victims are most often African-Americans, carry a hefty cost. They can poison relationships between police and the community, limiting cooperation in the fight against crime, the mayor and police officials say.

These stories certainly paint an informative background for the protests over the death of Freddie Gray, who had his vocal chords crushed and his spine severed after being taken into police custody.

New York City

Amongst other flaws, the NYPD is most recently infamous for the killing of Eric Garner, an unarmed Black man who was put into a chokehold by a detective. Garner’s death highlights the collective community frustration with two models for urban policing that have been fully embraced by the NYPD: stop-and-frisk, and Broken Windows.

The idea that stop-and-frisk reduces crime was substantially disproven after courts declared that New York City’s implementation of the policy was unconstitutional and disproportionally affected minorities. A drastic reduction in the number of stops has had no impact on NYC crime rates — in fact, crime has continued to decline. Nonetheless, Police Commissioner Bill Bratton has doubled down on a similarly discriminatory policy: Broken Windows policing.

The basic idea of Broken Windows policing is that penalizing small infractions — such as vandals breaking a window — discourages higher-stakes crime. Matt Taibbi describes it thus:

The ostensible goal of Broken Windows is to quickly and efficiently weed out people with guns or outstanding warrants. You flood neighborhoods with police, you stop people for anything and everything and demand to see IDs, and before long you’ve both amassed mountains of intelligence about who hangs with whom, and made it genuinely difficult for fugitives and gunwielders to walk around unmolested.

But the psychic impact of these policies on the massive pool of everyone else in the target neighborhoods is a rising sense of being seriously pissed off. They’re tired of being manhandled and searched once a week or more for riding bikes the wrong way down the sidewalk (about 25,000 summonses a year here in New York), smoking in the wrong spot, selling loosies, or just “obstructing pedestrian traffic,” a.k.a. walking while black.

Ferguson

I would suspect that for many white, middle-class Americans, the sustained protests in Ferguson over the death of Michael Brown seemed disproportionate. The protests are more understandable, however, in the light of a Justice Department report describing the pervasive racism within the Ferguson police force. Offensive emails passed around freely within the department, unconstitutional stops and arrests, and excessive force… the pattern feels depressingly predictable at this point. In a story that almost defies belief, Ferguson police once wrongfully arrested a Black man after mistaking him for someone else, beat him bloody when he objected, and then proceeded to charge him with destruction of property for bleeding on their uniforms.

Two notable findings in the Justice Department report, however, are worth calling out: Ferguson’s local court system makes it unreasonably difficult to resolve municipal code violations, and also impose unduly strict penalties on individuals who are unable to make it to a court appearance or pay a fine.

John Oliver can explain the impact of municipal violations far better than I can. The entire video is worth a watch:

The Poverty Connection

We now take a detour from the blatant racism demonstrated within police departments across the country to take a closer look at the system that these officers operate within. Remember how Blacks are significantly more likely to be stuck below the poverty line than whites? Put together a system of Broken Windows policing, burdensome municipal violations, and a disproportionate percentage of Black arrests, and suddenly we’re talking about a significant percentage of the population that is extremely susceptible to being trapped in a vicious cycle of arrests and jail time.

Prison population has exploded since the 1980s, despite overall declining crime rates. Court systems across the country are overwhelmingly backlogged with cases. As a result, low-income individuals are under significant pressure to plead guilty, even if innocent of a crime. The choice between remaining in jail to fight a criminal charge and pleading guilty so as not to get fired for missing work is absolutely reprehensible, yet it’s a choice that thousands of people face each year.

None of this is to say that dealing with the justice system while poor is a problem exclusively limited to the Black community. Nonetheless, given the fact that nearly 1 in 3 Black people live in poverty, it would be disingenuous to pretend that this issue didn’t have a disproportionate impact on that community.

The War on Drugs Connection

According to a study by Kathleen Sandy, “In 2003 Black Americans then constituted approximately 12 percent of our country’s population and 13 percent of drug users. Nevertheless, they accounted for 33 percent of all drug-related arrests, 62 percent of drug-related convictions and 70 percent of drug-related incarcerations.”

Similarly, the ACLU notes:

African-Americans do not use drugs more than white people; whites and blacks use drugs at almost exactly the same rates. And since there are five times as many whites as blacks in the United States, it follows that the overwhelming majority of drug users are white. Nevertheless, African-Americans are admitted to state prisons at a rate that is 13.4 times greater than whites, a disparity driven largely by the grossly racial targeting of drug laws. In some states, even those outside the Old Confederacy, blacks make up 90% of drug prisoners and are up to 57 times more likely than whites to be incarcerated for drug crimes.

A drug-related conviction can effectively eliminate a person’s eligibility for housing assistance, food assistance, education grants, and a number of other poverty-alleviating programs. In other words, the exact programs that are critical to allowing an individual to return to society are the ones that they are no longer eligible for as the result of a drug conviction. This impact is amplified by the fact that Black offenders are 40% less likely to get a job offer than a white offender. In short, it is hardly surprising that recidivism is so high amongst these groups.

Other Thoughts

Author Alice Goffman spent 6 years living in a neighborhood in Philadelphia, exploring the “Kafkaesque” legal system that entraps Black men at a young age and pushes them towards the fringes of society, often on the run from the police. She writes:

The danger a wanted man comes to see in the mundane aspects of everyday life, and the strategies he uses to avoid or reduce these risks, have some larger implications for the way he sees the world, the way others view him, and consequently the course his life may take. At a minimum, his hesitancy to go to the authorities when harmed leads him to become the target of others who are looking for someone to prey upon. His fear of the hospital means that he doesn’t seek medical care when he’s badly beaten, turning instead to underground assistance of questionable repute.

More broadly, a man in this position comes to see that the activities, relations, and localities that others rely on to maintain a decent and respectable identity become for him a system that the authorities exploit to arrest and confine him. Such a man finds that as long as he is at risk of confinement, staying out of prison and maintaining family, work, and friend relationships become contradictory goals: engaging in one reduces his chance of achieving the other. Once a man fears that he will be taken by the police, it is precisely a stable and public daily routine of work and family life, with all the paper trail that it entails, that allows the police to locate him. It is precisely his trust in his nearest and dearest that will land him in police custody. A man in legal jeopardy finds that his efforts to stay out of prison are aligned not with upstanding, respectable action but with being a shady and distrustful character.

Former police officer Redditt Hudson contemplates:

On any given day, in any police department in the nation, 15 percent of officers will do the right thing no matter what is happening. Fifteen percent of officers will abuse their authority at every opportunity. The remaining 70 percent could go either way depending on whom they are working with.

That’s a theory from my friend K.L. Williams, who has trained thousands of officers around the country in use of force. Based on what I experienced as a black man serving in the St. Louis Police Department for five years, I agree with him. I worked with men and women who became cops for all the right reasons — they really wanted to help make their communities better. And I worked with people like the president of my police academy class, who sent out an email after President Obama won the 2008 election that included the statement, “I can’t believe I live in a country full of ni**er lovers!!!!!!!!” He patrolled the streets in St. Louis in a number of black communities with the authority to act under the color of law.

Putting It All Together

Systemic racism in law enforcement is a highly complex topic, and honestly, I feel like I’ve only scratched the surface in a very rambling sort of way. At the end of the day, I believe it’s incorrect to try to boil it down to “all cops are racist” — I just don’t think that’s true. However, the way our legal system has evolved over the years means that it’s extremely easy for a small percentage of individually racist cops to have a disproportionate negative impact on their communities. There is also the significant percentage (probably even the majority) of officers who are just doing their jobs and enforcing the law. Unfortunately, as we’ve touched upon in this post, there are some really fundamental issues with the laws that are being enforced — thus, those officers are helping to perpetuate a system that is creating an invisible underclass of criminalized poor and minorities.

It’s really easy for me to say “we need to root out the bad cops and change the system so the good cops can do their jobs better.” However, I haven’t been on the receiving end of law enforcement, and I’d imagine that getting stopped and frisked still feels humiliating even if the officer who’s frisking you isn’t racist.

The one thing I do know is this: we need to fundamentally rethink criminal justice in America, and critically examine whether we’re truly the post-racial society that we think we are. Otherwise, I fear that we will be unable to reverse course and empty the prisons that have been filled in such an unjust manner.