Healthcare Is Too Expensive. Here’s Why.

On a topic as broad and multifaceted as healthcare, it’s a little bit challenging to break down the issues and address them in a systematic manner. While it’s commonly known that the US spends far more on healthcare than any other nation, there are vast disagreements about the cause of the problem — or if there’s even a problem at all. After all, if we assume that better healthcare is more expensive, then why wouldn’t we want to pay more if it meant we achieved better outcomes?

The reality is that when it comes to healthcare, we’re not getting what we’re paying for. First, we’ll set the stage by cataloguing some commonly perceived reasons as to the potential cause(es) of the problem. Then, we’ll address the solutions proposed by both Democrats and Republicans, and see why both parties fall miserably short of achieving real reform. Lastly, we’ll take a look at some of the biggest culprits of excess healthcare spending, and various strategies that might actually help fix the problem.

Yes, Virginia, We Spend Too Much On Healthcare

This chart comparing per capita healthcare spending to per capita GDP is pretty revealing. For most nations, wealth is a fairly accurate indicator of how much is spent on healthcare, which makes sense. However, the US spends drastically above the average. As of 2006, we spent $646 billion dollars more than what you’d expect a nation of comparable wealth to spend on healthcare. Studies have shown that wealthier nations generally spend disproportionate amounts of money on healthcare, but the US outpaces even those other disproportionate spenders.

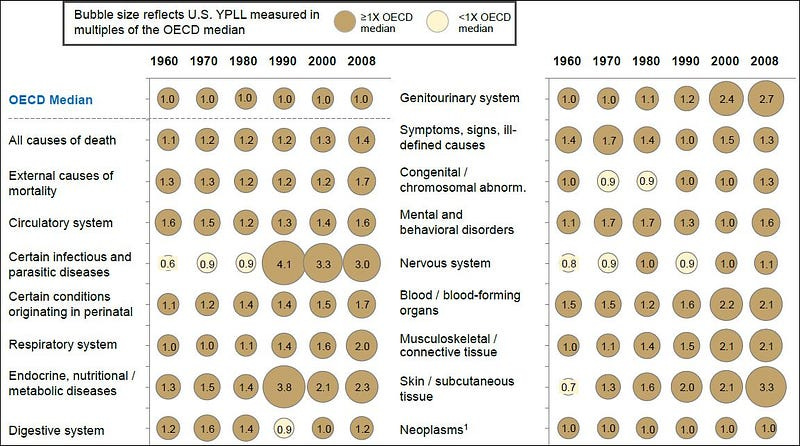

Given the fact that our healthcare spending is significantly above the expected amount, it would be reasonable to expect that we would be significantly healthier as well. Unfortunately, the data suggests otherwise. The following bubble chart shows US health metrics compared to other industrialized nations in the OECD. Any value <1.0 means we performed better than average, any value >1.0 means we performed worse. On virtually every single metric, US healthcare outcomes are significantly worse than average:

So yeah. There’s definitely a problem.

Things That Surprisingly Aren’t The Main Problem

Before I continue, I want to make something absolutely clear. While many of the issues I’m about to cover are not the primary driver of rising healthcare costs, that does not mean they aren’t problems. If you bought an item at a store for $100 and you have one coupon for 1% off and another coupon for 25% off, it’s obviously better if you can use both coupons. But if you’re picking which coupon you want to apply, it’s a no-brainer to go with the 25% off coupon. By the same token, when looking at healthcare reforms, it make sense to prioritize the biggest money-savers.

Malpractice and Defensive Medicine

A lot of people (particularly Republicans) point to malpractice lawsuits and defensive medicine as one of the primary causes of soaring health spending in the US, and believe that tort reform will correct the problem. In a medical context, tort reform means passing a law that limits the amount of money that can be paid out in a malpractice lawsuit. The underlying theory behind this is that if “ambulance chasers” don’t have a huge financial incentive to sue doctors over dubious claims, we will be able to reduce the number of malpractice lawsuits, which will in turn lower malpractice insurance premiums for doctors and make them feel less obligated to over-treat their patients with expensive tests and procedures.

While a philosophical case could be made that we should enact tort reform regardless and reduce the stress burden on doctors, unfortunately, it won’t result in significant healthcare cost savings. In 2008, total costs of defensive medicine were estimated to be approximately $55.6 billion, or a mere 2.4% of all healthcare spending. Another study indicated that a 10% reduction in malpractice insurance premiums would reduce total treatment costs by less than 1%, even when factoring in a corresponding reduction in defensive medical practices. And that doesn’t even affect other expense areas.

As a matter of fact, even without tort reform, malpractice insurance is becoming less of an issue. One physician reported that his annual malpractice insurance premium has dropped from $8,000 per year in 2003, to just over $3,000 per year. He’s not alone. Not only have malpractice claim payouts continued to drop, but doctors’ insurance premiums have dropped for seven consecutive years. Clearly this isn’t the silver bullet we’re looking for.

Pharmaceuticals

Rising drug costs are a problem. There’s certainly no doubt about that. In 2011, the US pharmaceutical market was estimated to be about $328 billion (out of $2.7 trillion in total healthcare spending.) Interestingly, Americans actually use fewer (less?) drugs than their counterparts in other nations — but we pay significantly more for them. There are a couple reasons for this: we tend to favor new (and accordingly more expensive) drugs, as a wealthy nation we inherently subsidize drug R&D for poorer nations, and our government does not control pharmaceutical prices as they might in a single-payer healthcare system. Basically, we’re helping to pay for the drugs sold in Europe and other parts of the world.

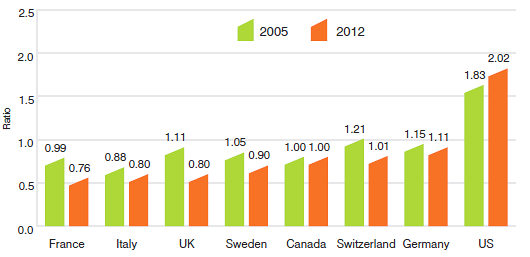

An idea known as drug reimportation is an interesting solution for this. Take a look at the chart below, which compares what Canadians pay for drugs compared to other nations. In other words, if a single dose of Aspirin cost $1.00 in Canada, that same dose would sell for $2.02 in the US. Imagine if it was possible to buy a thousand Aspirin in Canada, bring them home to the US, and sell them at near-Canadian prices. Obviously the price of the drug in the US would decrease. How much could we save overall with this strategy?

Purely as back-of-the-napkin math, if we know that the total US pharmaceutical industry size was $328 billion, and assume we could buy all those drugs at Canadian prices instead of US prices, that would slash the total pharmaceutical spending by about $164 billion. Of course, that’s a really optimistic number. The reality is that drug companies would probably either force other countries to raise the price of the drug, or simply stop selling it anywhere there were cost controls. Also, compare $164 billion to $2,700 billion (the total amount of all our healthcare spending.) The best-case scenario here is that we save about 6% of the overall total.

Unhealthy or Aging Population

Fact: healthcare for the elderly is more expensive than healthcare for younger people. Myth: the US has way more elderly people than other nations, and that’s why healthcare is so expensive here. Compare the percentage of our population over age 65 compared to other nations:

[caption id=”attachment_749" align=”aligncenter” width=”889"]

% Population Over 65[/caption]

We have a younger population than many other developed nations. We also smoke and drink significantly less, which has positive health benefits as well. Yes, our population is more obese than most other nations, which is a risk factor for certain diseases. But is that driving up healthcare spending? A McKinsey study suggests otherwise:

[caption id=”attachment_750" align=”aligncenter” width=”586"]

Disease Prevalence in the US Compared to Other Nations[/caption]

In other words, we’re younger and have fewer diseases than other nations, and yet we spend significantly more on healthcare with worse outcomes. It would be hard to design a crappier system than that.

Overutilization and Uncompensated Care

Overutilization is a basically a nicer way of saying Americans are hypochondriacs. Because we have some of the best healthcare facilities in the world, the reasoning goes, we’re much more likely to rush to the doctor when we think something is wrong. As a matter of fact, we visit the doctor less, go to the hospital less, and stay in the hospital for shorter periods of time than the OECD average.

[caption id=”attachment_753" align=”aligncenter” width=”705"]

Healthcare Utilization In OECD Nations[/caption]

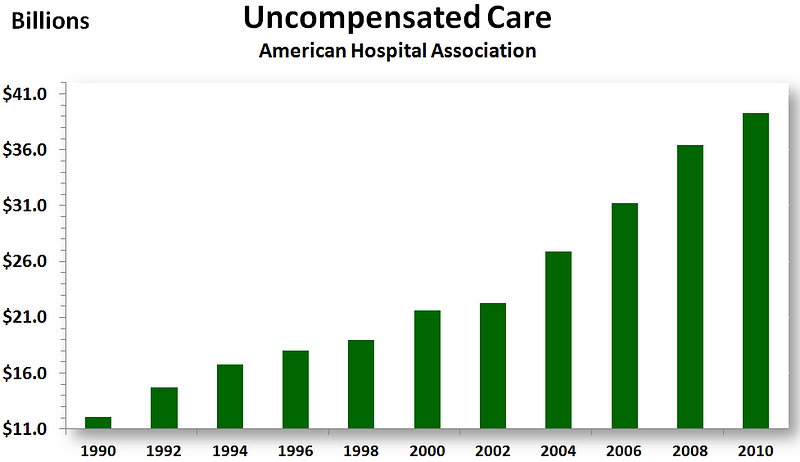

When you can’t pay for a trip to the doctor or ER, but receive treatment anyways, that is considered uncompensated care. Hospitals provide a certain amount of charity care, and then uncollectible bills are eventually written off as bad debt. This has to be having an impact on healthcare spending, right?

[caption id=”attachment_754" align=”aligncenter” width=”977"]

Uncompensated Care[/caption]

$40 billion isn’t trivial. But again, we’re comparing this to $2.7 trillion. In other words, if we could shift those costs back to the individuals using the care, we’d all save about $0.01 per dollar of healthcare spending. More importantly, it doesn’t actually reduce the overall amount being spent on healthcare, only who is paying for it.

As an aside, this more or less disproves the common Republican cry that “illegal immigrants are driving up healthcare costs because they get treatment and don’t pay for it!” They’re included in the numbers above.

Administration and Waste

There’s certainly a lot of overhead involved in the healthcare system. A lot of healthcare administrators earn egregiously outsized salaries as well: the president of MD Anderson Cancer Center earned $1,845,000 in 2012. The CEO of Mercy Hospitals (a non-profit organization) earned $1,930,000, and 7 other executives from the same organization all earned over a million dollars in 2012 as well. There are also costs associated with processing insurance claims, and potential losses due to fraud.

I was actually astonished when I discovered that Medicare appears to be… wait for it… actually more efficient than many private insurers when it comes to processing claims. According to research done by TIME Magazine:

Medicare’s total management, administrative and processing expenses are about $3.8 billion for processing more than a billion claims a year worth $550 billion. That’s an overall administrative and management cost of about two-thirds of 1% of the amount of the claims, or less than $3.80 per claim. According to its latest SEC filing, Aetna spent $6.9 billion on operating expenses (including claims processing, accounting, sales and executive management) in 2012. That’s about $30 for each of the 229 million claims Aetna processed, and it amounts to about 29% of the $23.7 billion Aetna pays out in claims.

You may argue that I’m comparing wasteful apples to even more wasteful oranges. It’s a fair point. While adding private insurers to the healthcare mix does create an inherently more expensive system, it turns out the US is actually fairly efficient, spending $19 billion less than you’d expect us to spend on administrative costs in 2006:

[caption id=”attachment_756" align=”aligncenter” width=”577"]

Health Administration Spending[/caption]

A significant chunk of spending by private insurers goes sales and marketing. So, while this results in their expenses being higher than Medicare’s, there is actually an overall benefit to the system.

How about fraud and abuse? According to the Economist, that cost us between $125 and $175 billion in 2009:

[caption id=”attachment_757" align=”aligncenter” width=”595"]

Healthcare Waste in 2009[/caption]

That’s absolutely something that needs to be addressed, but unfortunately, it’s just a symptom. The $250 billion in unnecessary care is interesting though. That’s a pretty hefty number, and it’s strongly related to the main underlying problem. We’ve arrived at the heart of the issue, the reason why our healthcare system is such a miserable failure.

The Healthcare Cartel

Imagine going into a car dealership to purchase a new car. Due to agreements that this dealership has made with other dealerships, they’re the only ones in this city who can sell a car to you. “How much is that Toyota?” you ask the dealer. “I’ll tell you once you’ve purchased it,” he responds. You know this dealership has a reputation for selling high-quality cars, so you agree to make the purchase. The dealer promptly hands you a bill for $120,000. On it are itemized charges, like $40 for windshield wiper fluid, $20,000 for each seat, and so forth. Shocked, you tell the dealer “there’s no way I can pay this!” He responds, “no problem, how about you pay $20,000 instead? That’s the price that almost everyone else ends up paying. We just keep the really high price for rich people who can pay cash.”

If that sounds like a great way to purchase a car, then you’ll love navigating medical bills in the US.

We Have No Idea What Healthcare Is Worth

Researchers at the University of California San Francisco tried to determine what an appendectomy with no complications (considered one of the most straightforward surgical procedures) would cost. Their answer? An amount varying between $1,529 and $186,955. By and large, the amounts charged were not dependent on geography, i.e. the affluence of the surrounding community.

In another study, orthopedic surgeons were only able to accurately estimate the cost of a hip replacement only 20% of the time. Think about that. The very person providing you a service has no idea how much their service actually costs. Part of this is due to the fact that medical device manufacturers generally make hospitals sign pricing NDAs before selling anything to them. This lack of price transparency gives the manufacturers increased leverage when bargaining with other hospitals. When something like a knee replacement component costs between $1,797 and $12,093 directly because of a hospital’s ability to strike a deal, this is a huge problem.

This is just one example of how healthcare in the US is an unfair market. Device manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies sign pricing NDAs with hospitals. Hospitals sign pricing NDAs with insurance companies. The system is essentially built to keep information out of our hands and make the process as one-sided as possible. In a normal market, if I didn’t want to pay a particular company’s price, I’d just go to a competitor. In medicine, that’s generally not possible. If I need an emergency appendectomy, I can’t really to try to compare different hospitals and see which one will provide the best bang for my buck.

We’re Being Insanely Overbilled

There are many models for determining how much a hospital should bill someone. Some hospitals will bill you based on your length of stay, while others bill based on the services they provide you. With the exception of Medicare, if you have insurance that’s accepted at a particular hospital, it means that your insurance company has negotiated a payment deal with that hospital. The dynamics between the bargaining power of the hospital and the bargaining power of the insurance company mean that two people receiving identical treatment may receive vastly different bills.

California actually has one of the more transparent systems for tracking healthcare billing and payments. Some researchers took a look at the amount billed by hospitals, compared to the amount of money they actually received:

[caption id=”attachment_760" align=”aligncenter” width=”412"]

Amount Billed vs. Amount Received[/caption]

While the amount being billed to patients has doubled since 2003, collected revenues have only gone up by about a third. Does this mean that hospitals are hemorrhaging money? Not in the slightest. In 2011, the total net profit for all 364 California hospitals was $5.8 billion, or about $16 million per hospital.

This phenomenon isn’t only limited to California hospitals. Nationwide, hospital revenue is generally about a third of the total amount billed. And non-profit hospitals are consistently more profitable than for-profit ones, which is totally screwed up when you think about it.

Let’s assume for a moment that hospitals actually billed what they expected to make in revenue. Americans spent about $900 billion last year on hospital care alone, not including primary care or prescriptions. That means our national healthcare spending would drop from $2.7 trillion dollars per year to $2.1 trillion per year, or a savings of around 22%. Not bad.

The Markup Is Ridiculous

Because the US healthcare system operates under a fee-for-service model, providers are unfortunately incentivized not only to bill for every little item, but also to charge disproportionate prices as well. The chargemaster is a relatively unknown document, but every single hospital has one, and it dictates the prices that go on each bill — with little connection to actual costs. A few examples from TIME’s report on healthcare spending:

1 generic Tylenol for $1.50. A box of 1,000 is available on Amazon for $13.49, or less than $0.01 apiece.

A diabetes test strip for $18. A box of 50 is available on Amazon for $27, or about $0.55 apiece.

A gown for the doctor performing the surgery for $39. You can purchase 30 of these online for $180, or $6 apiece.

Bacitracin, a common antibiotic, for $108. A 1-ounce tube is available on Amazon for $2.

A back muscle stimulator implant (the actual device itself, not the associated surgery) for $49,237. The implant is available wholesale for $19,000.

Don’t forget, all of these items are being charged for on top of the provider’s facility usage fee. Again, this points to the fact that individuals cannot act like rational consumers in the healthcare market. Assuming I’m even conscious to make the decision, am I going to refuse application of an antibiotic ointment because it’s going to cost me $108? Of course not.

This, of course, only addresses what hospitals are charging on top of the prices they pay to medical device manufacturers and Big Pharma, but suffice it to say that both those industries are doing exceedingly well.

It Ain’t A Free Market

Something I’ve alluded to several times is the fact that healthcare isn’t a free market. Most states still have Certificate of Need laws, which essentially forbid new healthcare providers from entering a market unless there is a proven “need” that cannot be met by existing providers. The patent system ensures that pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers don’t have to compete on price (and I haven’t even touched on the kickbacks to doctors who only recommend and use certain products.) Because most individuals get insurance through their employer, they have absolutely no say in the bargaining process over their discounts from healthcare providers. And so on, and so forth.

When an industry can charge whatever it wants, and when there are no alternatives, that seems to me to more or less fit the definition of a cartel. I say a cartel and not a monopoly, because a significant amount of this structure is propped up by the industry itself, not by government regulation. No government agency is forcing hospitals to sign NDAs with insurance providers or medical device manufacturers, but they do it anyways, because everyone (except the patient) wins. The hospital gets its markup, the manufacturer gets its profits, and the insurer gets to pay $5,000 while still counting the full $100,000 medical bill against your insurance limits.

Solving The Problem

Sorry, Democratic friends, the Affordable Care Act isn’t a panacea. As Steven Brill of TIME notes:

There is little in Obamacare that addresses that core issue or jeopardizes the paydays of those thriving in that marketplace. In fact, by bringing so many new customers into that market by mandating that they get health insurance and then providing taxpayer support to pay their insurance premiums, Obamacare enriches them. That, of course, is why the bill was able to get through Congress.

The ACA is actually attempting to accomplish two different things. The first and most contentious objective is getting more people insured. Yes, this will raise premiums through increasing the number of previously uninsurable individuals who now qualify, eliminating lifetime caps on insurance payouts, and so forth. As more low-income individuals receive insurance, usage of expensive emergency care will actually rise:

Low-income individuals are likely to attach a high “time cost” to primary care visits. Relative to their middle- and high-income counterparts, these patients face greater barriers when it comes to taking time off of work for a scheduled appointment, arranging transportation, child care, and the like. The hospital might offer easier access than outpatient clinics, and, in the emergency department, it’s less likely that they’ll be asked to return for follow-up visits.

Some argue that there is a moral imperative to making sure that healthcare is available to everyone. I’m not here to debate the merits of that. All I will note is that if as a nation we agree that we want more people insured, there is an associated cost to that. More importantly, it will do little to address the overall burden of healthcare spending: 70% of individuals with medical debt are already insured.

What Obamacare Gets Right

One of the bigger positive changes implemented by the ACA is changing how Medicare reimburses hospitals for care. Instead of paying for each element of the treatment separately, Medicare pays for patient outcomes, and creates financial penalties for errors. Ultimately, patients don’t care what drug is used to treat them, or what surgery they receive. They just want to get better. For example, by penalizing hospitals with high readmission rates, Medicare is reporting that they’re seeing a corresponding decrease in (expensive) patient readmissions.

Accountable Care Organizations also have the potential to save a significant amount of money. ACOs are groups of doctors that get paid based on their patient outcomes, rather than the number of tests they run. Bloomberg reports that this is already saving hospitals millions of dollars.

In short, we’ve been long overdue for a paradigm shift when it comes to spending on healthcare. Early data from the Congressional Budget Office and PricewaterhouseCoopers suggests that a slowdown in spending since 2011 can be attributed to these changes, though it’s too soon to say for sure.

What Still Needs To Be Done

Before the creation of the Manufacturers’s Suggested Retail Price (MSRP), it was impossible to know what a car was worth, and if a dealer was charging you too much. We need to create the healthcare equivalent of an MSRP. The Oklahoma Surgery Center serves as a fantastic model of what this could look like. When you go on their pricing page, you see the exact price that you’ll pay for each surgery — and that price is astonishingly low. More needs to be done to address the lack of price transparency.

Along with price transparency, hospitals need an economic incentive to bill patients according to the true value and cost of the care they are providing. This is particularly the case for non-profit hospitals, which are currently more profitable to run than for-profit hospitals. Medicare is actually quite good at determining what it actually costs a hospital to provide a given service, which suggests the possibility of taxing healthcare providers on the amount they bill above Medicare prices. Excluding emergency care, doctors don’t have to accept Medicare, so the fact that an increasing number of physicians are accepting Medicare suggests that it’s not unprofitable to provide services at those prices.

And of course, all the other issues we mentioned (which aren’t the main cause of soaring healthcare costs, but contribute to it) need to be addressed as well. I think it’s safe to say that if we could magically get the perfect law through Congress without it being tampered with by lobbyists, we could easily see savings of close to 30–40% of our total healthcare spending.

Conclusion

In all honesty, I’ve barely scratched the surface when it comes to how broken the US healthcare system is. My research has also thoroughly terrified me, because I’ve realized that whether or not you have insurance, having a major health incident in America virtually guarantees that you will be financially ruined for the rest of your life.

On a brighter note, I’ve also discovered that there are many non-partisan goals that both Democrats and Republicans should be able to agree are good. Whether or not you think the government should provide insurance for everyone who can’t afford it, hopefully we can all agree that overbilling patients is bad.

I’m putting all my sources at the end here. Some of them I highly recommend reading in full, so I’ve separated those out at the top.

Recommended Reading

What makes the US health care system so expensive

Other Sources

Accounting for the cost of US health care: A new look at why Americans spend more

A Primer On Hospital Accounting and Finance For Trustees and Other Healthcare Professionals

Malpractice Claims at Record Low, Not Driving Health Costs: Consumer Group

Low Costs Of Defensive Medicine, Small Savings From Tort Reform

The Pricing Of U.S. Hospital Services: Chaos Behind A Veil Of Secrecy

Quora: What are the ways to contain medical costs in the US without a single payer system?

New research shows Medicaid increases ER trips. Oregon has a plan to stop that.

The latest results from Oregon aren’t actually very counterintuitive

About 80 percent of hip doctors have no idea how much a hip replacement costs

How much does an appendectomy cost? Somewhere between $1,529 and $186,955

Availability of Consumer Prices From Philadelphia Area Hospitals for Common Services

Think America has the world’s best health care system? You won’t after seeing this chart.

Health Care Certificate-of-Need (CON) Laws: Policy or Politics?

High and Varying Prices for Privately Insured Patients Underscore Hospital Market Power

It Doesn’t Matter Whether Obamacare Is Causing the Health Spending Slowdown

Obamacare-Hating Pundit Asks, ‘When Has the Left Ever Cared About Facts’?

Affordable Care Act Section-by-Section Analysis with Changes Made by Title X and Reconciliation

Health reform at 2: Why American health care will never be the same

Photo: Flickr